To see how much these tactics are very much unchanged despite years of what may be perceived as intellectual progress in the fourth estate, one need look no further than George Orwell’s 1946 essay, ‘The Prevention of Literature; stimulated in part by the recent wartime strictures of reporting and partly by the acquiescence of the British left to a self-censorship or denial of utilitarianism that allowed them to indulge in a fantasy that the Stalinist propaganda emerging from Russia was to be counterbalanced by a publication by the Soviets of the truth when the ‘crisis’ was over. In it, he described an attitude that chimes with some resonance with the response to Snowden and others on a personal level.

‘The enemies of intellectual liberty always try to present their case as a plea for discipline versus individualism. The issue truth-versus-untruth is as far as possible kept in the background. Although the point of emphasis may vary, the writer who refuses to sell his opinions is always branded as a mere egoist. He is accused, that is, either of wanting to shut himself up in an ivory tower, or of making an exhibitionist display of his own personality, or of resisting the inevitable current of history in an attempt to cling to unjustified privileges.’

Jeffrey Toobin in the New Yorker calls Snowden ‘a grandiose narcissist who deserves to be in prison’. The Al-Jazeera journalists imprisoned in Egypt, along with political scientist Amr Hamzawy facing charges over a tweet questioning a court ruling, will undoubtedly find themselves accused of arrogance and narcissism during interrogation and court cross-examination. Just as patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel, a claim that the truth is already revealed and that the errant hack is indulging in a selfish fantasy by publishing a different perspective is the last gasp of a regime in a state of flux, struggling to establish absolute control after recent political upheavals.

There are three types of censorship that restrict the freedom of the press. The first is a blatant characteristic of the straightforward out-and-out totalitarian regime as practiced in China (although this is beginning to change) or South Korea - a complete ban on all un-licensed reporting that is filtered through a bureaucracy that can close down a paper or arrest a journalist without any justification beyond the state’s desire.

The second is the self censorship forced on journalists by law, bureaucratic regulation, and politically motivated criminal investigations as in Russia. This is the unkindest cut of all but at least allows journalists to do all they can to find more and more inventive ways of coding the truth into oblique, parody or clearly understood satire that test the very limits of the repressive laws. The same is true of censored literature, although the fact that repression produces great books, (Bulgakov’s Master & Margarita et al) should not be a reason to perpetuate the habit.

Finally there is the most insidious form of censorship. The ‘death by a thousand cuts’ as represented by exemplars such as post-apartheid South Africa’s 2004 Law on Anti-terrorism that permit authorities to restrict reporting on the security forces, prisons, and mental institutions. A recent Protection of Information Bill initially permitted the South African government to classify a wide range of information—including “all matters relating to the advancement of the public good” and “the survival and security of the state”—as in the “national interest” and thus subject to significant restrictions on publication and disclosure. It mandated prison terms of 3 to 25 years for violations and did not allow a “public interest” defence. Even in its revised form, any whistle blowing reporting that would ‘directly or indirectly benefit a foreign state or non-state actor or prejudice national security’ can lead to a prison sentence. Plus ca change.

This form is also represented by the Miranda case where the use of an obscure clause of terrorism legislation leads to a seemingly glacial encroachment on investigative journalism that creeps up on our liberties and engulfs them piece by piece.

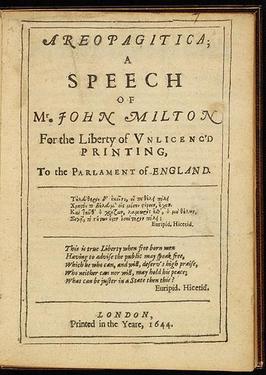

Orwell mentions attending a meeting of the PEN club to celebrate the tercentenary of John Milton’s anti-censorship tract Areopagitica. It is now 370 years since that template for the freedom of the press and of writers in general was published at the height of the English Civil War in opposition to the Licensing Order of 1643 and it seems we are still fighting to defend its precepts. As the appeal against the Miranda verdict is prepared, the blind seer’s words ring out over the centuries and echo around the corridors of power. ‘Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties.’

RSS Feed

RSS Feed