You know, at the start of some conversations, where they are going to go. As if following a well-worn track down a path you have travelled far too many times, you find yourself unable to stop putting one foot in front of the other down the highway to a place you have seen before and did not care for. Those conversational cul-de-sacs you disdain as the destination of intellectual featherweights with off-the-peg opinions on every subject. All the harder to accept when you see the path opened by others and fail to resist waltzing in yourself. You take the bait and you go there, even though alarm bells ring in your head and some small voice whispers in your ear, ‘Shut up. You have borrowed someone else’s clothes and dressed up in them even though they are full of holes and stink of laziness’.

In an age of perpetual digital din, where maintaining an interlocutor’s interest above their smartphone is an achievement, the art of genuine conversation, an exploration of wit or ideas that provoke and stimulate, is almost impossible. In fact, the intellectual rigour Coleridge or Hume applied to such an extent that they held salons entranced is now expended on simply finding some small gap in which to place a half-baked observation or Twitter derived witticism.

But although the growth of communications technology exacerbates the difficulties, this has always been one of the eternal verities since we progressed from prehistoric grunt to Wildean epigram. The avoidance of the mundane, the repetition of a thought that appears ubiquitous but has not been analysed, remains a daily intellectual battle that fences constantly with convention and politeness.

Quentin Crisp observed that if you apply the avoidance of clichéd conversation, then you are defined by it. Fewer people tax you with them and do not expect the usual empty infelicities from you. ‘Nobody ever talks to me about the weather’ opined the Englishman from New York. So very un-English.

I speak as an arch exponent, a past and present offender, not as a reformed dullard whose every utterance is an aphorism, every riposte a devastating intellectual thrust. Back in the eighties, a grubby invitation to throw a cliché party was the subject of modern art. The very fact that it was labelled ‘modern’ art implied the disapproval of the man on the Clapham Omnibus. And we all like to be regarded as him, don’t we? Look in your heart and ask yourself whether you have ever started a conversation with a disavowal of your contribution before you even belch it out. ‘I’m only a layman, but…, I’m just an ordinary bloke, but…’ as if being alive and not at the centre of every subject gives you a right to weight your argument with a built in withdrawal mechanism, ready to press the negate button as soon as your inelegant theory is assailed by an impudent fact.

I went to Rome for the first time early in 1985 and visited an American screenwriter called Stephen Geller whose masterly adaptation of Vonnegut’s ‘Slaughterhouse-Five’ won the Jury prize at Cannes in 1972 and is set to be unjustly eclipsed by Charlie Kaufman’s remake in 2015.

Steve arranged for my wife and I to stay in a small hotel close to the Pantheon in a small room with a roof terrace at the top of a long staircase where Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward always resided when visiting the city. It overlooked another roof terrace belonging to the apartment of Gore Vidal that was ringed with tiny bay trees. It was summer, and no doubt we English remarked upon the weather as if we were discovering it for the first time.

Steve’s apartment was at the top of a stunning 17th century house located in the historic via Beatrice Cenci, between "Campo dè Fiori" and the Piazza Navona. We were invited to dinner and sat drinking 20 year old grappa which I was unable to distinguish from grappa made the previous Tuesday.

Just before we were to sit down at the table, a telephone call and a ring on the buzzer heralded the arrival of a Cuban fireball called Ana Mendieta. She was short, lithe, beautiful and drunk as a skunk. Wait, we are trying to avoid clichés here. She was a glittering anchovy marinated in perfumed spirit, wriggling and flashing in the shallows before us, just out of reach. And drunk as a skunk.

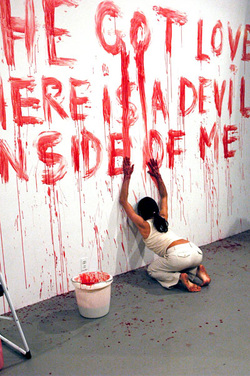

I found out later she was a performance artist, sculptor, painter and video artist who had made her name with ‘body art’, reclining naked in landscapes covered in mud, stones, branches or feathers. One startling video work sees her holding the jerking body of a decapitated chicken as the blood spurts across her belly and groin until it hangs, drained and inert after the frenetic death throes pulsing through her scarlet hands. In fact, I came to know that much of her work somehow touched upon the violence, abuse and objectification of women.

That day, she showed us a catalogue of her exhibition of ‘art objects’ - sculptures of clay and earth arranged or thrown on the ground and highly coloured. She sat between my wife and I at dinner and supplemented her earlier consumption with some wine as she chattered animatedly in a scandalising fashion that was both beguiling and confusing.

I learnt that she and her sister had been sent to the States by her parents from Havana to escape Castro’s regime and had spent the first years in refugee camps before being fostered in Iowa. Her father had been imprisoned for his involvement in the Bay of Pigs debacle that so nearly wiped out the planet before I was even born.

I was 24 years old and ill-equipped for most conversations, let alone ones on modern art. But the path had been opened by Ana and I walked blindly in.

Although Equivalent VIII, usually referred to as "The Bricks", was bought by The Tate Gallery from minimalist artist Carl Andre in 1972, it was only noticed by the Sunday Times and the Daily Mirror (‘What a load of rubbish’) in 1976 when an article debased and derided the purchase of such a work with taxpayer’s funds and ensured this perspective dominated all conversations on the value of minimalist or conceptual art to this day.

The exhibit comprises one-hundred-and-twenty fire bricks, arranged in two layers, in a six-by-ten rectangle. Primed with my off-the-peg opinion, I understood that Andre had not constructed the work himself but had sent it to the gallery in a packing case with each brick labelled and accompanied by a diagram of how they should be placed.

I speculated in what I imagined to be a waggish manner on what would have happened if the curators had inadvertently misplaced a brick. Would the work then be regarded as valueless or could he sue the gallery for producing its own plagiarised limited edition of his work? The man on the Clapham Omnibus brayed his disdain, bolstered with all the authority of a memory of a conversation with someone who had actually read the article or seen the work.

There was an uncomfortable silence before Steve, intensely amused said quietly, ‘Ana has just got married to Carl Andre.’ I reached for some more grappa, not caring if it was older or younger than me and my dumb mouth.

The conversation moved on and I felt perhaps I had been forgiven when I felt Ana’s hand under the table moving up my leg and resting companionably on my upper thigh. Afterwards I discovered that she was doing the same with her other hand to my wife, so perhaps affection rather than absolution was on her mind.

After dinner, she offered to drive us back in her battered Volkswagen, but reluctant as I was to say goodbye to the lively life-affirming sensuality of La Mendieta, I didn’t want to be wrapped around a bollard. I kissed her cheek and whispered an apology. ‘De nada, kid’ she said and smiled.

In September, back in London, a tiny square of text in the London Evening Standard stated baldly that Carl Andre had been arrested for the murder of his 36 year old wife Ana Mendieta who had fallen 34 floors to her death from the balcony of the Greenwich Village apartment they shared. Sounds of an argument had been heard just before and several friends remarked on Ana’s fear of heights.

Andre was tried and acquitted in 1988 in a controversial trial which still reverberates today with some saying Ana was volatile and prone to suicidal thoughts and others saying Carl was the OJ of the art world.

Either way, all I could think about was how much life and vitality she exuded and how my only response to all that was a mundane cliché of a conversation on a warm and gilded Roman night.

Andre is, as I write, 77 years old and says in interview that his mind has been destroyed by alcohol but still entrances with his conversation. Ana and he certainly both drank a fair amount on the night of her death. Both were passionate artists and volatile spirits whose conversations, I can imagine, were not often beset by cliché.

The trial turned up a poem of Carl’s that was considered significant at the time.

The ways of love were

sometime my revenge when

I was wronged by something

done or said & she stood

naked by the window waiting

to be struck perhaps where

her white breasts were red

No one knows what happened the night Ana fell, but I’m guessing neither of them was guilty of discussing the weather.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed