The novel has as the central premise a man waking up in the body of a homeless man in the 21st Century in a broadly contemporary version of our own world, claiming to be Eric Arthur Blair who wrote under the pseudonym of George Orwell and died in London in 1950.

One question that came up in the talk has occurred before in another context when a TV producer asked ‘Why doesn’t Eric wake up in the world of his own novel 1984?’ It’s a fair question as this is probably what you would expect when you read the premise of the book. The answer is that I was totally uninterested in that scenario because it would almost write itself. Eric would wake up as Winston Smith working in the Ministry of Truth and suffer interrogation by O’Brien in a world that would probably look as close to Terry Gilliam’s ‘Brazil’ as you can get. You know how that novel would develop and so do I. I’m sure there is a novel writing machine somewhere that could do it. But not this fleshy tube of chemicals.

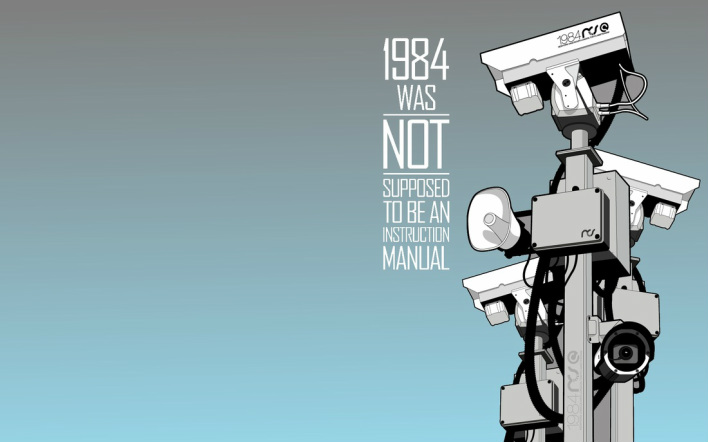

Instead the book forces Eric to confront all the issues we deal with concerning surveillance, a disengaged democracy and a Big Data world where, far from being forced to give up personal privacy, the populace actively volunteers it in order to engage with social media and commerce. That makes his journey a little more unpredictable and also occasionally funny. The abiding characteristic of Orwell’s ‘1984’ is that it is resolutely gloomy; a fact that he acknowledged and attributed to his declining health at the time he wrote it. Me, I don't have a terminal diagnosis and tend to enjoy a lot of very satisfying biscuits whilst writing so consequently, I am not a literary icon and a more frivolous writer. In my book, Eric struggles to survive in a world that seems familiar to us at first but soon appears to have moved slightly further on in our present drift towards a total surveillance society.

It is, of course, the height of audacity to attempt to speak in the voice of one of the world’s most celebrated literary icons. Everyone feels that they own him and they have their own idea of what his voice sounds like, what he might think and how he might express himself. I have a Houdini-like escape clause for this perfectly understandable sentiment. The man who wakes up in an alley in my book believes himself to be Orwell. But it is possible, of course, that he is deluded or ill. As he says to a Judge in the book whilst appearing in court over his detainment under the Mental Health Act:

‘I really don’t know if what I now believe is what I have always believed. As I have no memory of this existence and this place, I cannot truly determine whether I am deluded or dreaming. If the former, it appears a curiously convoluted fantasy rooted in an arcane knowledge of an all too well documented life. If the latter, then nothing you recommend about what people choose to call my ‘care’ will make any difference at all. We occupy two opposing perceptions of existence, my Lord. To you, I am an ex-army petty offender with a medical record and a history as Harold Lewis Allways. To me, I am who I have always been; or, at least, who I now perceive myself to have always been. More prosaically, I can’t convince you that my perception is any more valid than yours. On the other hand, you cannot convince me that I am anything other than Eric Arthur Blair. We are, as far as I am concerned, in a stalemate position, existentially.’

You’ll have to read the book yourself to make up your own mind about whether Eric really is awake.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed